THE SAVING SIGN. Thoughts on Holy Cross Day September 14th 2025

One of the most sacred sites in Essex is the simple Chapel of St. Peter on the North Sea shore at Bradwell. It is all that remains of a more extensive monastery which was originally built there by St. Cedd. He was one of twelve Anglo-Saxon boys who had entered the monastery at Lindisfarne, founded by St. Aidan. It was the Irish custom to build monasteries in remote places and there to train up young people to be apostles for Christ. St Aidan, trained on Iona adopted this practice with the Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria

Once trained, they were sent out to proclaim the Good News of Jesus Christ. So, St Cedd left Lindisfarne and sailed down the North Sea coast before landing, in 654 AD, at Bradwell. Here he founded a monastery and from where the Gospel was proclaimed to much of Essex.

The Chapel of St. Peter at Bradwell has enjoyed mixed fortunes, even for a time being used as a barn but today it is a simple reminder of the Gospel coming to Essex.

Its interior is of breathtaking simplicity, the only adornment being a beautiful Cross, designed by the Church artist, Francis William Stephens.

On it are painted figures of The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John and above the figure of Christ is a depiction of the Hand of God in an act of blessing. St. Cedd kneels at the foot of the Saviour. On either side of Christ are the faces of St Peter and St. Paul. Christ is shown with a halo marked by the cross and his arms are outstretched in blessing. This is a figure not of grotesque suffering but of triumphant victory.

It is an artistic representation of the Crucified as shown to us by St. John for whom the Cross is a sign of Triumph – of a completion of the saving work of Father and Son. Michael Ramsey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, commenting on St. John’s portrayal of the Passion of Christ says that on Calvary Christ ‘Reigns’ as he accomplishes his Father’s will and fulfils the Scriptures. This was his moment of supreme glory.’

Michael Ramsey makes the comment:

“Calvary is no disaster which needs the Resurrection to reverse it, but a victory so signal that the Resurrection follows quickly to seal it.”

Celtic/ Anglo-Saxon Christianity which fed the soul of St. Cedd was inspired by St. John’s understanding of the Cross. The Cross was seen as the ‘Saving Sign’ and its victory dominated spirituality and mission. They had a firm belief in the power of the Cross to transform hearts and lives.

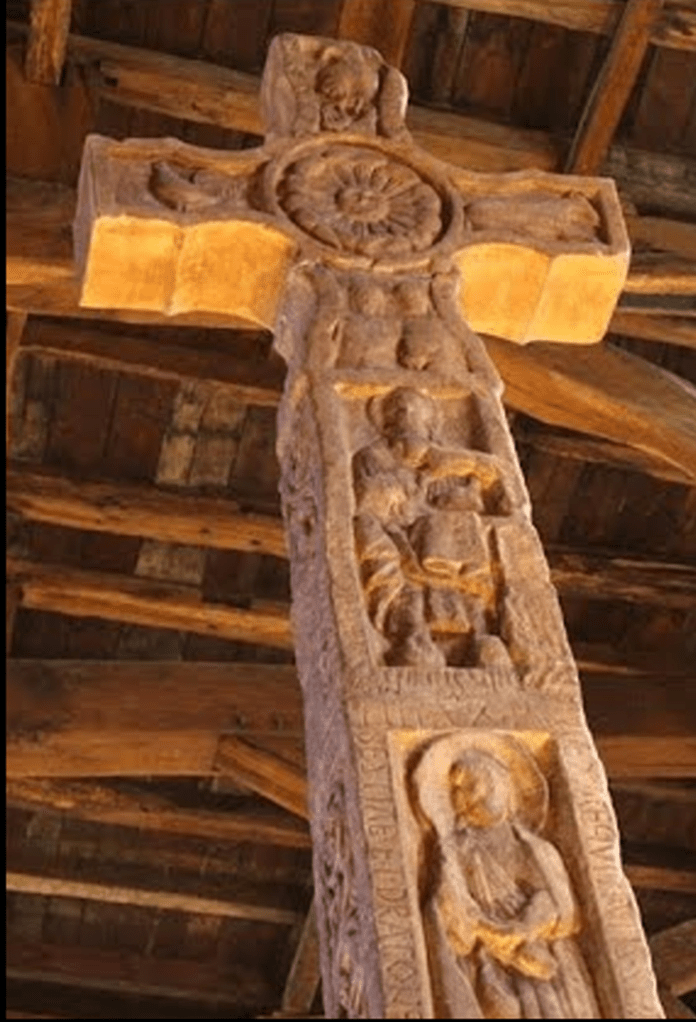

Visitors to ‘Celtic’ countries like Ireland, Scotland and Wales will be familiar with the High Crosses, elaborately carved with biblical scenes from both Old and New Testaments all contained within the form of the Cross. These were (and still are) sermons in stone offering the onlooker a way into Scriptural truths of Salvation brought to our world by Christ. They are the Waymarks for the soul’s spiritual journey marking out the earth for God and leading the people towards eternal life.

They were often preaching posts – wayside pulpits at which the missionaries stood and proclaimed the Gospel and claimed souls for Christ.

I think of the magnificent Ruthwell Cross in Dumfrieshire which is carved with Old & New Testament scenes. It stands today in a small church, rescued from oblivion by a Church of Scotland minister at the end of the 19th century, but it once stood on the shoreline, a gathering point for those who would hear of Christ’s triumph and Victory of the Cross preached to them by monks from as far away as Lindisfarne and Durham.

It is unique also because carved around the edges are Anglo-Saxon Runes which depict part of the oldest English poem, The Dream of the Rood.

When Cedd came to Essex, he came in the power of the triumph of the Cross. He sailed from Lindisfarne and by tradition he would adopt the Irish custom of placing the Cross of Christ in the prow of his boat so that he was constantly reminded in whose name and service he sailed.

No doubt, like so many Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Christians he practiced the Cross prayer – which involved hours of standing with arms outstretched in the Cross position.

Celtic praying included a gathering at the Cross for daily prayer. An eighth century monastic rule says:

“The monks should follow the head monk (abbot) to the cross with melodious chants, and with abundance of tears flowing from emaciated cheeks”, in imitation of a daily prayer office sung in Jerusalem at the Church of the Resurrection – the church built by the Emperor Constantine which gave rise to today’s special observance of the Holy Cross.

Hymns would be sung and the people would move slowly around the Cross – not unlike what happens today in modern Taizé which has done much to restore the Cross to the heart of Christian devotion.

Hardly surprising that the Cross has such a central place in the worship at Taizé which was born out of the ravages and destruction of a war- destroyed Europe and which preached Reconciliation as its central message.

As the stone crosses reclaimed Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Britain, so Europe was reclaimed for God and the hearts of the people led back to Christ. As the problems in the Ukraine, Gaza and other troubled areas of the world are showing us that reclaiming for God is on-going and always vital. We must go on proclaiming that the Victory of the Cross overcomes all evil. It is this Victory which is the about love transforming a disfigured and at times enslaved humanity.

As a prayer from Taize puts it:

Through the repentance of our hearts,

And the spirit of simplicity of the beatitudes,

You clothe us with forgiveness, as with a garment.

Enable us to welcome the realities of the Gospel

With a childlike heart,

And to discover your will,

Which is love and nothing else.

Here we are brought to the heart of the Cross’s message – the Victory of love. Not only sin and death are defeated by love but also those other things which afflict our lives and drag us down. In the face of evil, pain, hurt and uncertainty, the Cross becomes a protection – the Saving Sign.

There is a Passiontide Prayer which includes the lines:

Yea, by this Sweet and Saving Sign,

Lord, draw us to our peace and thine.

[Mr G]

Photo: Mr G