BLACK LIVES MATTER

Lewis Hamilton continues to draw attention to injustices towards Black people (and others) through his high profile anti-racism demonstrations at Formula 1 meets.

It is obviously something he feels deeply involved in and because of his celebrity status, the T shirts he wears and the actions he takes are powerful statements which remind us that, as far as human rights towards black and other ethnic groups, we have a long way to go.

However, whilst that is true, we have also come a long way and in the midst of much negativity about the way White people, especially those with power, have failed to work for change – not least a change of heart – there are those whose actions have made a difference.

There are many who, over the years have been working quietly and not so quietly to celebrate and promote the dignity, equality, integrity and joy of being a motley collection of people who populate this planet Earth – a planet which we share both with each other and with the Creation of which we are supposed to be ‘stewards’ not ‘lords’. Being stewards means we take responsibility for caring for, developing and enriching the Earth. This includes all peoples who share the gift of our beautiful world. Currently we are thinking particularly of displaced people who have been made refugees through no fault of their own. Many are suffering after being made homeless on the island of Lesbos when their camp was destroyed by fire. Other refugees drown in the Channel. All of them as much part of the human race as we are.

Yet, whilst we all have much to repent of in our failures in stewardship, care, and the fight for justice, we also have things to celebrate. We can all think of the likes of Mother (now St) Teresa of Calcutta, Desmond Tutu, or Oscar Romero in his battle for the rights of people in El Salvador.

I want to mention, however, two particular men for whom Black Lives Mattered so much that they were prepared to lay their lives on the line in different ways but for the same purpose. They wanted those who suffer injustice, indignity, oppression and a lack of kindness to know that there are people who value and care for them.

They refused to accept the lot of those whom many would cast to the outer edges of society. Both are or were members of the Anglican Church and, as someone put it,

It is probably a truth that the Church makes her most powerful statements of faith from the margins of society rather from the centre of it.

My thoughts about these things are encouraged by my friendship with Patrice and her son, Ty. Patrice is from Jamaica but her heart was made in heaven. However, it was in a book compiled by The Rt. Revd. Alan Smith, bishop of St. Albans to honour the holy people who have associations with that Diocese, that, on Holy Cross Day (14th) I was reminded about, Trevor Huddleston.

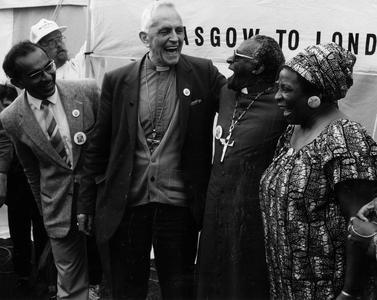

Bishop Trevor Huddleston sharing a joke with Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Long ago he played a significant part in my own faith journey but that is for another time. His entry in ‘Saints and Pilgrims’ gives us the reason why he is so important for the Black Lives Matter movement and for all who seek not only to right wrongs towards Black people and other ethnic groups, but actually to celebrate with them our common humanity.

Trevor Huddleston is ‘remembered for his tireless campaign against Apartheid.’ Many, like me, grew up with a knowledge of Apartheid—the insidious doctrine of separation which not only kept the races apart in South Africa but also ensured that most black and ‘coloured’ people lived in abject poverty.

The entry goes on to say that his costly prophetic ministry in South Africa, was a long way from his Bedford roots, and his education at Lancing College and Christ Church, Oxford. After that, he trained for ordination at Wells Theological College and then, perhaps as a surprise to many, he joined the Community of the Resurrection, an Anglican religious community based, as it still is, in Mirfield, West Yorkshire. The Community eventually sent him to a mission station at in Rosettenville in Johannesburg, South Africa. As the Priest-in-Charge of the CR’s Anglican Mission in Sophiatown and Orlando, Huddleston ministered in the townships between 1943 and 1956.

Amongst the people he had dealings with was Nelson Mandela with whom, together with another Anti-Apartheid leader, Oliver Tambo, he developed a great friendship. His ministry there has been described as a courageous witness against the evils of Apartheid but, on the positive side, his was a witness to a common heritage that makes us equal and mutually dependent on each other. His fight for Black people often took the form of protest and dispute but deep in his heart was a love of people that simply wanted to make them feel important, cared for and helped. The people responded to his deep kindness and battling on their behalf by nicknaming him, Makhalipile, which means ‘the one who is fearless.’

Nelson Mandela said of him: ‘Father Huddleston walked alone at all hours of the night where few of us were prepared to go. His fearlessness won him the support of everyone. No-one, not the gangster, tsotsi, or pick pocket would touch him.’

Of course, he made enemies – some powerful proponents of the Apartheid philosophy. There was a growing concern for his safety and the Community of the Resurrection recalled him back to Mirfield. His heart was made heavy by the decision but as a monk he had taken a vow of obedience.

His struggle for justice continued, however, not least through lobbying powerful politicians but also through the writing of a book, ‘Naught for your Comfort.’ Published in 1956, it almost didn’t see the light of day. He managed to get the manuscript out of the country just 24 hours before all his papers were seized by the authorities for whom he had become a massive thorn in the flesh.

In the book he tells of his ministry to thousands and he gives a moving account of their struggles to make good and his determination to help them do so. At the time, Apartheid was little understood in Britain. This book was therefore explosive, all the more so because it was not so much about the theory of Apartheid as about what it was doing to human beings who just happened not to be White.

Trevor Huddleston returned to Africa twice more, first as Bishop of Masasi in Tanzania and, after a spell as Bishop of Stepney, later as Bishop of Mauritius and Archbishop of the Indian Ocean – a role that was less about preaching to the waves and more about loving the communities nearby!

When he retired he returned to Mirfield but he was to make one further journey to Africa: Father Huddleston died on 20 April 1998 at his home in Mirfield but his ashes were interred next to the Church of Christ the King in Sophiatown. As he lived, so in death he remained a ‘Citizen of Africa’ – something he was proud of.

He was given many honours but I suspect the greatest was to be known as one who, in a destructive society filled with hate for Black people who were the true natives there, brought love and kindness, two simple but powerful qualities which change the world. For Trevor Huddleston both stem from his own experience of being held in the love and care of God whom he simply served. It was a love and a care which flow through the suffering of Jesus on the Cross through to the glory of the Resurrection. It was no accident that God had called him to become a ‘Mirfield Father’ of a community that has, as its symbol, the Resurrection Lamb.

Alongside Trevor Huddleston, in a different way is the witness of another remarkable priest, Gonville ffrench-Beytagh. I was privileged to meet him when I was a theological student. I have never forgotten him, nor his witness to the Gospel.

Gonville ffrench-Beytagh with Archibishop Michael Ramsey

He isn’t heard of these days but he was the Anglican Dean of Johannesburg. Apartheid was then at its height in South Africa. Gonville ffrench-Beytagh commited a terrible crime: he dared to give Communion to whites and blacks kneeling together at the same altar rail. He was arrested and sent into solitary confinement. He was fed on salted beef, given little water and every minute the light in his cell flicked on and off. He was isolated and the aim was to break him as a human being.

He almost went mad but he said that his faith had saved him. In a cell where he had nothing, he regularly celebrated the Eucharist. He had no bread or wine and no prayer book but he recited the service from memory and meditated on Scripture which had, over long years of study, impregnated his soul. He spoke of the moment of Communion, when he took nothing into his hands and received no sacrament, as one of the most spiritual experiences of his life. It was then that he felt the power of prayers being said for him throughout the Christian world.

In this he has been an encouragement during the time of lockdown when Christians also haven’t been able to meet together. There has been for many a discovery of ‘spiritual communion’ rather as Gonville ffrench-Beytagh experienced it. Through God’s grace it was deeply valid for him as it has been for us for at its heart is Jesus’ presence.

In giving Holy Communion to Black and White people kneeling together, he was making a statement of how God views his children on earth. All are welcome, loved and accepted as equals. Gonville ffrench-Beytagh’s action might have challenged the authorities, leading them to act. (There is a precedent for this in the Gospel of course.) I think, however, that he was simply saying ‘God loves all of you. I love all of you. Jesus died for you and rose again. This Eucharist is the place where you all meet to celebrate that. That is quite a powerful witness!

Both Trevor Huddleston and Gonville ffrench-Beytagh are people who stood up for the truth that Black Lives Matter and whilst there is an inevitable sense of protest about that, what really matters is less about demonstration and more about loving action. When Black and White and Brown and Pink and every rainbow hue meet together and recognise each other’s worth and the need we have for each other, then maybe we will learn the importance of being kind to each other, cherishing and treasuring what is special in our mutual, common and eternally-bound lives.

I think that would gladden the hearts of Trevor and Gonville very much indeed.

[GC]

The local worthies of Sunderland Point and Overton could not agree that he should be buried in the churchyard because he was a heathen and unbaptized. The sailors took his body, therefore, and dug a simple grave about a few yards beyond the village.

The local worthies of Sunderland Point and Overton could not agree that he should be buried in the churchyard because he was a heathen and unbaptized. The sailors took his body, therefore, and dug a simple grave about a few yards beyond the village.