Copyright © 2017-2025 Dicasterium pro Communicatione – All rights reserved.

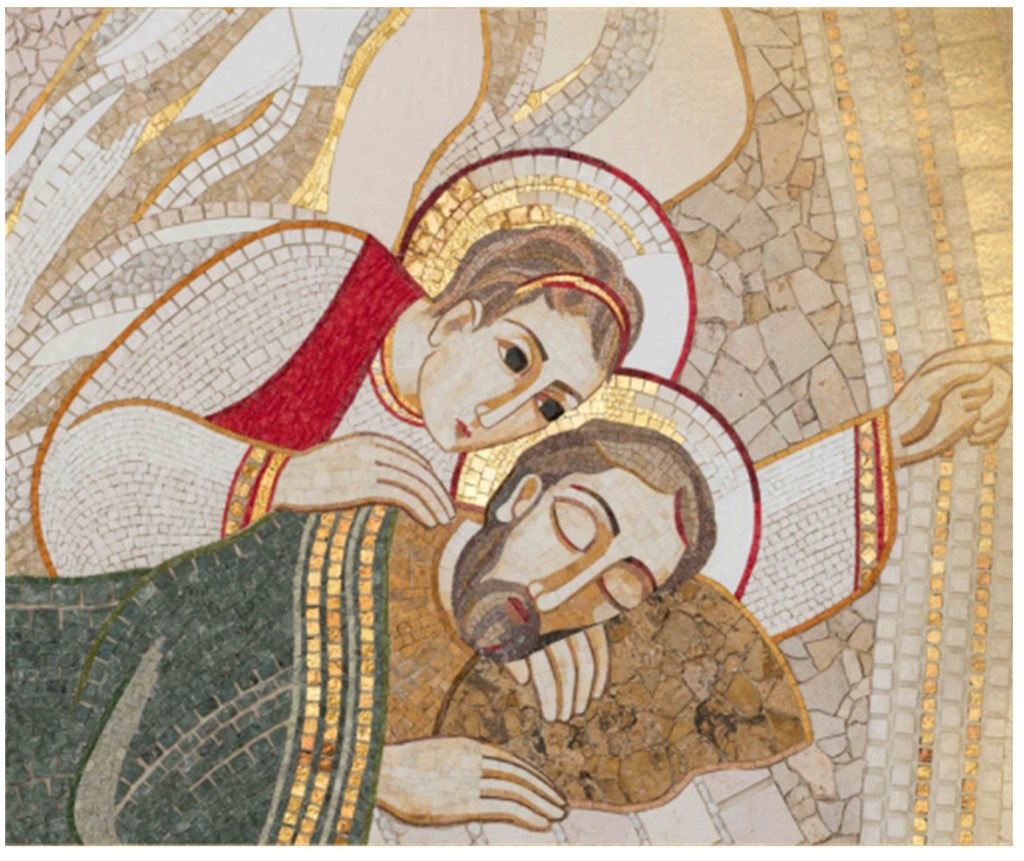

On March 19th, the Church remembered St. Joseph, husband to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Though often rather like the ‘man in background’, Joseph played a vital and significant role in the birth of Jesus and did so in obedience to the will of God.

God communicated that will through the message of an angel and did so on 4 occasions. These dreams are all narrated by the writer of St. Matthew’s Gospel. (Chapter 1 verse 18ff, and Chapter 2)

In the first dream the angel assures Joseph that, despite his misgivings, it is God who has chosen him to be Mary’s husband and watch over her as she is pregnant with the son of God, Jesus. He is to be the protector, guide and provider of love and security to the Holy Family, to Jesus in his infancy.

The other dreams are instructions from God. In the 2nd dream, Joseph is warned to flee with Mary and Jesus when King Herod ordered the massacre of the innocent babies and young children in order to do away with the one who might be a threat to Herod’s kingdom. Joseph flees to Egypt. The third dream tells Joseph that Herod’s death means it is safe to return home but the 4th dream tells Joseph that there is still some possibility of harm so Joseph must avoid Judea and settle instead in Galilee.

Taking the theme of the first dream, a friend wrote a poem which she gave to me as a special gift. I have her permission to make it known to others, so here it is.

Joseph’s Carol ~ An Angel called my name

Blessed am I, blessed of all men.

When dark had quenched the light of day

A holy angel came; an angel called my name

I am not good, not free from sin,

Yet, as I slept and dreaming lay

An angel called my name.

A simple artisan, someone

Of humble birth, thinks not to see

A holy angel bright. An angel came that night

Through cool moonlight to sleeping world,

From cloud-streaked sky to speak to me,

An angel came that night.

Though humble, yet I count as one

Whose lineage of David came.

The angel seemed so near: the angel voice was clear:

“And Mary shall bring forth a Son.

God wills that Jesus be his name”

The angel voice was clear.

And when that Holy Child was born,

In Bethlehem, of David’s line,

The angels came to see. The angel melody

the dark sky filled. So from that dawn

I played my part in God’s design.

Oh God. My thanks to Thee.

(by Julia Edmonds)

[Mr G]